- Introduction

- Motivation for scraping

- Scraping web pages

- Web scraping case study: LAS colleges in the US

- Pdf scraping with

pdftools

Introduction

This tutorial covers how to scrape data from webpages and PDF documents

using the rvest and pdftools packages in R. The introduction to the

HTML is a slightly modified version of the Web Scraping with

RVest

tutorial by Kasper Welbers, Wouter van Atteveldt & Philipp Masur.

Motivation for scraping

The internet is a veritable data gold mine, and being able to mine this data is a valuable skill. In the most straightforward situation, you can just download some data, for instance as a CSV or JSON file. This is great if it’s possible, but alas, there often is no download button. Another convenient situation is that some platforms have an API. For example, Twitter has an API where one can collect tweets for a given search term or user. But what if you encounter data that can’t be downloaded, and for which no API is available? In this case, you might still be able to collect it using web scraping.

A simple example is a table on a website. This table might practically be a dataframe, with nice rows and columns, but it can be hassle to copy this data. A more elaborate example could be that you want to gather all user posts on a web forum, or all press releases from the website of a certain organization. You could technically click your way through the website and copy/paste each item manually, but you (or the people you hire) will die a little inside. Whenever you encounter such a tedious, repetitive data collection task, chances are good you can automate it with a web scraper.

The idea of web scraping may seem intimidating, and indeed it can get

quite complex. However, the rvest R package simplifies the process

considerably by using intuitive, tidyverse-based workflows for

extracting data from HTML files. With this package you don’t need to

have a complete understanding of how the underlying HTML scripts of a

webpage are structured in order to extract data from the page.

Nevertheless, the next section introduces some basic concepts and

structures when it comes to HTML files in order to give you a better

understanding of what the rvest functions actually do.

Scraping web pages

HTML basics

The vast majority of the internet uses HTML to make nice looking web pages. Simply put, HTML is a markup language that tells a browser what things are shown where. For example, it could say that halfway on the page there is a table, and then tell what data there is in the rows and columns. In other words, HTML translates data into a webpage that is easily readable by humans. With web scraping, we’re basically translating the page back into data.

To get a feel for HTML code, open this link here in your web browser. Use Chrome or Firefox if you have it (not all browsers let you inspect elements as we’ll do below). You should see a nicely formatted document. Sure, it’s not very pretty, but it does have a big bold title, and two tables.

The purpose of this page is to show an easy example of what the HTML code looks like. If you right-click on the page, you should see an option like view page source. If you select it you’ll see the entire HTML source code. This can seem a bit overwhelming, but don’t worry, you will never actually be reading the entire thing. We only need to look for the elements that we’re interested in, and there are some nice tricks for this. For now, let’s say that we’re interested in the table on the left of the page. Somewhere in the middle of the code you’ll find the code for this table.

<table class="someTable" id="exampleTable"> <!-- table -->

<tr class="headerRow"> <!-- table row -->

<th>First column</th> <!-- table header -->

<th>Second column</th> <!-- table header -->

<th>Third column</th> <!-- table header -->

</tr>

<tr> <!-- table row -->

<td>1</td> <!-- table data -->

<td>2</td> <!-- table data -->

<td>3</td> <!-- table data -->

</tr>

<tr> <!-- table row -->

<td>4</td> <!-- table dat -->

<td>5</td> <!-- table dat -->

<td>6</td> <!-- table data -->

</tr>

</table>

This is the HTML representation of the table, and it’s a good showcase

of what HTML is about. The parts after the <!-- are comments and

therefore do not affect the layout of the website. First of all, notice

that the table has a tree-like shape. At the highest level we have the

<table>. This table has three table rows (<tr>), which we can think

of as it’s children. Each of these rows in turn also has three children

that contain the data in these rows.

Let’s see how we can tell where the table starts and ends. The table

starts at the opening tag <table>, and ends at the closing tag

</table> (the / always indicates a closing tag). This means that

everything in between of these tags is part of the table. Likewise, we

see that each table row opens with <tr>, and closes with </tr>, and

everything between these tags is part of the row. In the first row,

these are 3 table headers <th>, which contain the column names. The

second and third row each have 3 table data <td>, that contain the

data points.

Each of these components can be thought of as an element. It’s these

elements that we want to extract into R objects with rvest.

So let’s use this simple example site to go over the main rvest

functions.

Simple example with rvest

First load the rvest and tidyverse packages, and specify the URL of

the webpage we intend to scrape. You can define the URL within as a

separate object or inside the scraping function; since often you want to

scrape multiple pages in one workflow, it is good practice to specify

URLs outside the function.

library(tidyverse)

library(rvest)

url <- "https://bit.ly/3lz6ZRe"

The function to read the HTML code from a URL into R is read_html(),

with the URL as the function argument.

html <- read_html(url)

The result of this function is a list containing the raw HTML code, which is quite difficult to work with. So the next step is to extract the elements that we want to work with.

Elements can be selected with the html_element() or html_elements()

function depending on whether you want to access only the first item

matching the element specification or get a list of all fitting

elements.

By element specification we usually refer to CSS selectors that

categorize the object we want to extract. CSS is mostly used by web

developers to style web pages, but the CSS selectors are also a good way

to identify types of data such as tables or lists. Once we have the CSS

selector we are looking for, we can add it as the argument of the

html_elements() function, and extract only the parts of the HTML code

that correspond to the selector.

There are quite a lot of CSS selectors, and the table below gives some of the main examples. However, you don’t actually need to remember any of these, but instead you can use selector tools to extract the information you need.

| selector | example | Selects |

|---|---|---|

| element/tag | table |

all <table> elements |

| class | .someTable |

all elements with class="someTable" |

| id | #steve |

unique element with id="steve" |

| element.class | tr.headerRow |

all <tr> elements with the someTable class |

| class1.class2 | .someTable.blue |

all elements with the someTable AND blue class |

Instead of going through the raw HTML and trying to match up the code to the observed website, you can use a browser extension that tells you the CSS selector you’re looking for just by clicking on the part of the webpage that you’d like to select. In Chrome this extension is called Selector Gadget. You can simply search for the extension and install it, at which point you can use it on your chosen webpage by clicking on the extension in your list of installed browser extensions.

In the example webpage you can see that selecting the title gives you a CSS selector “h2” (which stands for level 2 header), while selecting any of the main text gives “p” for paragraph. Selecting elements can sometimes get a bit difficult with the gadget, and you can’t always get it to do exactly what you want: for example, it is hard to select the entire table and receive the selector “table”, as the gadget often tries to select subitems of the table such as “td” instead. If you can’t get the gadget to select what you’re looking for, it might be a good idea to go back to manually inspecting the HTML source code and looking for the element there.

If the selector gadget fails, the Inspect option of Chrome may be more helpful than viewing the full source code. Inspecting the page allows you to focus on particular elements, because when you hover your mouse over the elements, you can directly see the correspondence between the code and the page. The tree structure is also made more obvious by allowing you to fold and unfold elements by clicking on the triangles on the left. Therefore you can quickly identify the HTML elements that you want to select.

In this example let’s try to extract the table with the ID “#exampleTable”. Alternatively, we can extract both tables by asking for all “table” elements.

# Select the element with ID "exampleTable"

example_table <- html |>

html_element("#exampleTable")

The output looks a bit messy, but what it tells us is that we have

selected the <table> html element/node. It also shows that this

element has the three table rows (tr) as children, and shows the values

within these rows.

In order to turn the HTML code of the table into a tibble, we can use

the html_table() function.

example_table_tidy <- example_table |>

html_table()

Putting the whole workflow together, web scraping takes three main steps:

- load the full HTML code with

read_html() - extract the elements you need with

html_elements() - transform the HTML code to clean objects with e.g.

html_table()orhtml_text()

To get both tables into a list of tibbles, we can use the following code chunk:

tables <- read_html(url) |>

html_elements("table") |>

html_table()

Of course, in this case we worked with a very small and clean example,

so the tables list already contains clean tibbles. That is not always

the case, and often you need further data wrangling steps to clean up

variable names, data types, row structure, ect., but at that point you

can use standard tidyverse workflows.

As another example, you can extract and display the text from the right column of the example page:

read_html(url) |>

html_elements("div.rightColumn") |>

html_text2() |>

cat()

## Right Column

##

## Here's another column! The main purpose of this column is just to show that you can use CSS selectors to get all elements in a specific column.

##

## numbers letters

## 1 A

## 2 B

## 3 C

## 4 D

## 5 E

## 6 F

We used the html_text2() function to transform HTML code into plain

text (html_text2() usually creates nicer text output than

html_text()), and then used the cat() function to print it on the

screen.

Another nice function is html_attr() or html_attrs(), for getting

attributes of elements. With html_attrs we get all attributes. For

example, we can get the attributes of the #exampleTable.

html |>

html_elements("#exampleTable") |>

html_attrs()

## [[1]]

## class id

## "someTable" "exampleTable"

Being able to access attributes is especially useful for scraping links.

Links are typically represented by <a> tags, in which the link is

stored as the href attribute.

html |>

html_elements("a") |>

html_attr("href")

## [1] "https://blog.hubspot.com/website/how-to-inspect"

Web scraping case study: LAS colleges in the US

In the following we will work towards solving a hypothetical problem:

You’re starting a new liberal arts college, and there is one big unresolved question: what should the school colors be? You want to pick a nice set of colors, but you worry that some other colleges already use the same color scheme, and therefore your branding will be easily confused with existing colleges. Therefore you want to choose unpopular colors so your new college can stand out from the hundreds of existing liberal arts colleges. Unfortunately, there’s no comprehesive database of the school colors of liberal arts colleges. However, this information usually shows up on the fact sheet of each college’s Wikipedia page. In addition, Wikipedia also has a list of all LAS colleges in the US (see here).

Given that there are hundreds of LAS colleges, it would be extremely time-consuming to one by one open their Wikipedia pages and extract their school colors into a spreadsheet. However, Wikipedia pages are highly organized, so if we write a scraping script that works for the page of one college, it is likely to work for all colleges. In addition, the list of all colleges contains hyperlinks to the individual college pages, which makes it easy to create a list of the URLs we would like to access. Therefore, we can make a straightforward plan to tackle this initially quite intimidating problem.

- Look at a few example Wikipedia pages to understand where they mention the school colors.

- Write a scraping script that extracts the relevant information for a single college.

- Get a list of URLs for all colleges.

- Apply the scraping script repeatedly, changing only the URL.

- Merge the extracted information.

- Analyze/visualize the data.

Scrape the fact sheet of a single college

Let’s start by writing a scraping script for one college as a representative example. In this case, let’s use Amherst College, and try to extract the colors “white” and “purple” from the grey factsheet on the right hand side of the page.

The selector gadget shows us that we can extract the elements by

referring to “.infobox”. Instead of extracting the infobox as a table,

let’s extract the variable labels and values separately into two

character vectors, and combine them into a tibble afterwards. We can do

this by extracting “.infobox-label” and “.infobox-data” elements

separately, and converting them into character strings with

htlm_text2(). In this case this is a better approach than extracting

the whole table, because it gives us more control over the layout of the

tibble, which makes it easier to handle slight differences in the

different Wikipedia pages. You can also try to extract the whole

“.infobox” as a table, but you might need to take some additional steps

of data wrangling e.g. to fix variable names.

url <- "https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amherst_College"

html <- read_html(url)

label <- html |>

html_elements(".infobox-label") |>

html_text2()

value <- html |>

html_elements(".infobox-data") |>

html_text2()

factsheet <- tibble(label, value)

factsheet

## # A tibble: 28 × 2

## label value

## <chr> <chr>

## 1 Motto "Terras Irradient (Latin)"

## 2 Motto in English "Let them enlighten the lands[1]"

## 3 Type "Private liberal arts college"

## 4 Established "1821; 203 years ago (1821)"

## 5 Accreditation "NECHE"

## 6 Academic affiliations ".mw-parser-output .hlist dl,.mw-parser-output .hlist …

## 7 Endowment "$3.775 billion (2021)[2]"

## 8 President "Michael A. Elliott"

## 9 Academic staff "307 (Fall 2021)[3]"

## 10 Undergraduates "1,971 (Fall 2021)[4]"

## # ℹ 18 more rows

Find and clean the school color values

The resulting factsheet tibble indeed contains the school colors, but

also a lot of other information that we don’t need. In addition, the

cell containing the colors also has some HTML code that wasn’t removed

by the previous code. We might also want to make the color names more

consistent so we can count the number of occurrences more easily (so

e.g. we don’t have “Red” and “red” separately).

One idea for making the color references more consistent is to allow

only the colors that R recognizes. While this is not the only approach

and it will lead to a loss of information if a college uses a particular

shade not defined in R, this approach has a nice advantage: when we

visualize the distribution of colors, we can actually use the color

codes defined in R to add color to our figure. So let’s extract the

vector colors defined in R with the colors() function, and convert

this vector to a single string with the colors separated by |. Recall

from the workshop on regular expressions that | in a regex stands for

“OR”, so using the resulting r_colors string as a pattern will detect

any occurrence of an R color in a string.

r_colors <- colors() |> paste(collapse = "|")

Now we can move on to wrangling our factsheet tibble: let’s keep only

the row containing the color, and use string operations to extract the

colors appearing in the value variable.

By looking at the Wikipedia page, you might figure out that the weird “.mw-parser-output…” section of the value string refers to the displayed color squares. If that part didn’t contain any color references, there would be no problem with leaving it in the value, but notice that it specifies that the square border should be black. So if we extract all colors appearing in the text, we’ll mistakenly find that one of the school colors is black. So let’s remove the text creating these squares: it seems that it starts with “.mw-parser-output” and ends with “.mw-parser-output .legend-text{}” (normally you’d need to check the results from multiple different college pages to make sure that this pattern is consistent).

Once only the color (and some footnote references) remain in the cell,

we can extract the colors recognized by R using str_extract_all().

Note the use of str_extract_all() over str_extract() to make sure

that we extract all colors if a school has more than one colors.

The result of str_extract_all() is a variable of character vector

instead of single strings, which makes the variable quite hard to work

with. It would be better to have a row corresponding to every individual

color a school has – so we’d have two rows for Amherst, one with purple

and one with white. Then we can easily count how many universities use a

particular color. We can do this transformation by calling the

unnest() function, which expands the character vector to become

separate observations corresponding to each element of the vector.

factsheet |>

filter(label == "Colors") |>

mutate(value = str_remove(value, "\\.mw-parser-output.*\\.mw-parser-output \\.legend-text\\{\\}"),

known_color = str_extract_all(tolower(value), r_colors)) |>

unnest()

## # A tibble: 2 × 3

## label value known_color

## <chr> <chr> <chr>

## 1 Colors " Purple & white[5]" purple

## 2 Colors " Purple & white[5]" white

Get a list of colleges with Wikipedia links

Now that we have a scraper that should work for any LAS college Wikipedia page with the same structure as Amherst, we need a list of the URLs that we want to scrape. Conveniently, there is a Wikipedia page of a list of LAS colleges, which features a list linking to all individual college Wikipedia pages. So all we have to do is scrape that list and extract the URLs.

The selector gadget shows us that we can extract the list of schools with the element tag “#mw-content-text li a” – that is, we’re looking for elements of the content text that are both a list (“li”) and a hyperlink (“a”). Then we can extract the attributes of the hyperlink to get the URL from “href” and the school name from “title”, and combine the resulting vectors to a tibble.

Since there are a few links that have the same element tag as the school

links, but are not school links, we can filter the resulting list of

links by requiring that the link name includes “University” or “College”

– a quick look at the Wikipedia list shows that all schools meet this

criteria. In addition, looking at the URLs, you might notice that they

are relative links that only contain the subpage of Wikipedia. In order

to open the URL with rvest, we need to complete URL, so we should add

“https://en.wikipedia.org” to the start of each link – the paste0()

function does exactly that (it combines its arguments into a single

string, with no separator between them). The resulting list object is

a tibble with two columns: the name of all colleges and their

corresponding Wikipedia page URL.

url <- "https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_liberal_arts_colleges_in_the_United_States"

html <- read_html(url) |>

html_elements("#mw-content-text li a")

list <- tibble(url = html_attr(html, "href"),

name = html_attr(html, "title")) |>

filter(str_detect(name, "(University|College)")) |>

mutate(url = paste0("https://en.wikipedia.org", url))

Write a function for extracting the color given a link

We will cover writing functions in more detail later in the

apprenticeship, but for now let’s have a look at the example below. You

might notice that the code inside the same code we have seen before: we

extract the HTML code from a URL input, get the vector of infobox labels

and data, and combine them into a tibble, keeping only the URL and the

cell containing the color (notice that the url vector has a length of

one and therefore gets recycled in the tibble). By containing this code

within a function(){} argument, we make the code reusable: we can

rerun it just by calling the function name (in this case,

get_school_color) and the arguments we would like to use as inputs. In

the function definition these arguments are listed inside the

parentheses: in this case, the only argument is url so by calling the

get_school_color() function with a different url argument will run

the code in the function body (inside the curly braces), changing every

mention of url into the the new URL specified in the function

argument.

The example below shows how to use this new function to extract the

school colors of Amherst. Notice that if you run the function without

assigning the result to a new object, it prints the final tibble created

by the code in the function body. This happens because in the function

we don’t assign this final tibble to an object, therefore by default it

becomes the value returned by the function. In turn, if we assign the

outcome of the function to an object, then the resulting tibble of

colors gets saved to the R environment (notice that our function behaves

in the same way as pre-defined functions like sum() – printing the

result if the function is called, and saving it to the environment if

assigned to an object).

get_school_color <- function(url) {

html <- read_html(url)

label <- html |>

html_elements(".infobox-label") |>

html_text2()

value <- html |>

html_elements(".infobox-data") |>

html_text2()

tibble(url, label, value) |>

filter(label == "Colors") |>

select(-label)

}

get_school_color("https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amherst_College")

## # A tibble: 1 × 2

## url value

## <chr> <chr>

## 1 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amherst_College .mw-parser-output .legend{page-…

amherst_color <- get_school_color("https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amherst_College")

Get all school colors and visualize the distribution

So the next thing to do is to run the function we just defined for all

URLs that we have in our list object. Again, we will cover appropriate

functions for these repeated actions later, for now we’ll just learn how

to solve this particular challenge.

If you are familiar with other programming languages, you might consider

using a loop to run the function for every element of the url variable

of the list tibble. In R, however, loops are not the best solution in

many cases. Instead, the tidyverse contains a package called purrr

that contains functions that takes vectors and functions as its inputs:

it runs the function one by one with each element of the vector as the

function argument, and combines the results into a single object. In

this case, we can use the map_df() function to combine the results

into a dataframe (the map() function uses a list instead), and we can

take the vector of list$url as the potential arguments for the

get_school_color function. Since this single line of code opens and

scrapes hundreds of webpages, it can take a few minutes to run.

data <- map_df(list$url, get_school_color)

Once we have our data object that contains all the color information

extracted from the webpages, we can take some additional steps of data

cleaning in order to visualize the distribution of colors. We can simply

repeat the same steps that worked for the case of a single college.

First we create a string that defines all colors known to R, separated

by | to use as a regex pattern. Then we can take the data object,

and remove the HTML code creating the color squares, and use the regex

pattern to extract the colors recognized by R. The extra line in the

mutate function converts all occurrences of the color “navy blue” to

“navy” because otherwise R will extract “navy” and “blue” separately and

therefore inflate the occurrences of “blue” – you’ll notice issues like

this after you try to extract the colors and have a look at the results.

We again use the unnest() function to have a new row for every element

of the character vector of known colors. In addition, we merge the

results with the original list object so we can add the university

names as identifiers in addition to the URL, and keep only the name

and known_color variables, and only unique combinations of these

values. At this point you might also notice that grey and gray are

both accepted spellings of the same color, so we can replace one with

the other to make sure the spelling is consistent across colleges.

Once we have this colors tibble that contains the extracted colors for

each college, it is quite easy to count the number of times each color

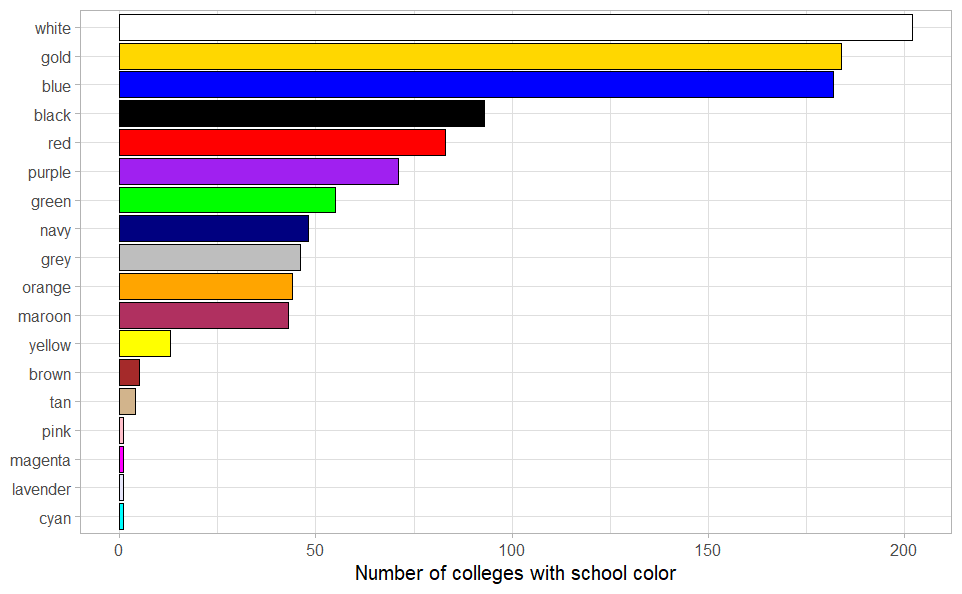

appears and plot the results on a bar chart. The fct_reorder()

function in the aesthetic specification arranges the values based on the

corresponding counts. As for the bars, instead of specifying the fill

as an aesthetic or a single value, we specify it as a character vector

that has the same length as the number of categories plotted. In this

case we can exploit the fact that the known_color variable already

contains color strings recognized by R, so by specifying the variable as

the colors we want to use, each bar will be filled with the color

corresponding to the category displayed.

r_colors <- colors() |> paste(collapse = "|")

colors <- data |>

mutate(value = str_remove(value, "\\.mw-parser-output.*\\.mw-parser-output \\.legend-text\\{\\}"),

value = str_replace(value, "[nN]avy [bB]lue", "navy"),

known_color = str_extract_all(tolower(value), r_colors)) |>

unnest(known_color) |>

left_join(list) |>

distinct(name, known_color) |>

mutate(known_color = ifelse(known_color == "gray", "grey", known_color))

color_counts <- colors |>

count(known_color)

ggplot(color_counts, aes(n, fct_reorder(known_color, n))) +

geom_col(fill = color_counts$known_color, color = "black") +

xlab("Number of colleges with school color") + ylab(NULL) +

theme_light()

The resulting plot shows how often each color is used as the school colors of a US liberal arts college. The results are not perfect, as not all hues are recognized and therefore extracted by R: for instance, “cardinal” (a shade of red) is used by 14 colleges, but the color is not defined in R, so there is no bar for cardinal, and neither does it contribute to the counts of “red”. Nevertheless, there is certainly evidence that if you want your hypothetical school to stand out, white, blue and gold are certainly bad options for the school color.

Pdf scraping with pdftools

Scraping pdf documents is useful for the same reason as scraping web pages: often you want to extract information from several documents with the same structure, and manually copy-pasting all that information would get very tedious. In addition, if you ever tried to copy information from pdf files, you might have found that sometimes line breaks in the pdf copy over, tables get messy, headers and footers copy end up in the middle of the text, or special characters are lost. Fortunately, there are a few R packages that make it easier to read pdf files into R as plain text. Unfortunately, these tools are not perfect, and therefore pdf scraping usually involves a quick and easy first step of importing the data, and a far longer step of extensive cleaning of the messy character strings you imported.

We will use the pdftools package, so let’s install and load it.

# install.packages("pdftools")

library(pdftools)

As an example, we look at a report on cancer rates in the Netherlands in 2020 that you can find here. Our goal is to extract the table on page 2, and visualize the data presented there.

We can extract all text from the report into R with the pdf_text()

function, which imports the contents of the referenced pdf file as a

character vector, each element containing all text on one page. If you

have a look at what the current 2nd page looks like, you can see that it

is a very messy character string instead of a nice table. Using the

cat() function to display the text more nicely also doesn’t make it

much better. But technically all the data is in R, so the importing step

is done.

pdf <- pdf_text("https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/populations/528-the-netherlands-fact-sheets.pdf")

pdf[2]

## [1] " The Netherlands\n Source: Globocan\n\n\n Incidence, Mortality and Prevalence by cancer site\n\n New cases Deaths 5-year prevalence (all ages)\n Cancer Number Rank (%) Cum.risk Number Rank (%) Cum.risk Number Prop. (per 100 000)\n Breast 15 725 1 11.9 10.75 3 283 3 6.7 1.64 67 477 784.82\n Prostate 14 580 2 11.0 9.75 2 976 5 6.1 0.92 61 096 715.65\n Lung 13 500 3 10.2 4.08 11 188 1 22.8 3.05 17 878 104.34\n Colon 11 887 4 9.0 3.25 4 730 2 9.7 0.99 36 117 210.78\n Melanoma of skin 8 310 5 6.3 2.89 906 17 1.8 0.24 29 557 172.50\n Bladder 7 417 6 5.6 2.07 1 811 7 3.7 0.33 25 162 146.85\n Rectum 4 845 7 3.7 1.53 1 787 8 3.6 0.42 16 171 94.37\n Non-Hodgkin lymphoma 4 105 8 3.1 1.32 1 462 10 3.0 0.33 13 624 79.51\n Pancreas 3 331 9 2.5 0.86 3 137 4 6.4 0.83 2 519 14.70\n Kidney 3 019 10 2.3 1.00 1 306 12 2.7 0.33 9 426 55.01\n Oesophagus 2 776 11 2.1 0.85 2 139 6 4.4 0.59 3 512 20.50\n Leukaemia 2 375 12 1.8 0.77 1 628 9 3.3 0.33 7 434 43.39\n Corpus uteri 2 202 13 1.7 1.44 537 18 1.1 0.27 8 981 104.46\n Stomach 2 099 14 1.6 0.60 1 240 13 2.5 0.29 3 553 20.74\n Lip, oral cavity 1 558 15 1.2 0.52 331 20 0.68 0.09 5 108 29.81\n Multiple myeloma 1 504 16 1.1 0.45 950 16 1.9 0.19 4 338 25.32\n Liver 1 494 17 1.1 0.41 1 446 11 3.0 0.40 1 518 8.86\n Brain, central nervous system 1 391 18 1.1 0.53 1 037 15 2.1 0.37 4 355 25.42\n Ovary 1 245 19 0.94 0.73 1 068 14 2.2 0.55 3 629 42.21\n Thyroid 873 20 0.66 0.34 178 24 0.36 0.04 3 410 19.90\n Testis 830 21 0.63 0.76 22 34 0.04 0.02 3 838 44.96\n Cervix uteri 773 22 0.59 0.63 253 21 0.52 0.15 2 472 28.75\n Larynx 738 23 0.56 0.26 247 22 0.50 0.07 2 630 15.35\n Mesothelioma 599 24 0.45 0.16 535 19 1.1 0.14 722 4.21\n Vulva 565 25 0.43 0.32 120 26 0.24 0.04 1 948 22.66\n Hodgkin lymphoma 461 26 0.35 0.20 81 28 0.17 0.02 1 953 11.40\n Oropharynx 439 27 0.33 0.17 187 23 0.38 0.07 1 394 8.14\n Anus 283 28 0.21 0.10 62 30 0.13 0.02 943 5.50\n Hypopharynx 245 29 0.19 0.09 94 27 0.19 0.03 503 2.94\n Gallbladder 210 30 0.16 0.06 131 25 0.27 0.03 267 1.56\n Penis 192 31 0.15 0.11 35 32 0.07 0.02 676 7.92\n Salivary glands 185 32 0.14 0.06 63 29 0.13 0.01 670 3.91\n Nasopharynx 79 33 0.06 0.03 43 31 0.09 0.01 286 1.67\n Kaposi sarcoma 75 34 0.06 0.03 1 35 0.00 0.00 259 1.51\n Vagina 70 35 0.05 0.04 25 33 0.05 0.01 212 2.47\n All cancer sites 132 014 - - 33.42 49 008 - - 11.26 461 066 2690.8\n\n\n Age-standardized (World) incidence rates per sex, top 10 cancers\n\n\n Males Females\n\n Breast 100.9\n\n Colorectum 48.4 34.3\n\n Prostate 73.9\n\n Lung 34.3 33.5\n\n Melanoma of skin 27.1 27.4\n\n Bladder 27.3 8.1\n\n Non-Hodgkin lymphoma 14.4 9.2\n\n Kidney 11.6 5.6\n\n Leukaemia 9.5 6.3\n\n Pancreas 8.1 6.8\n\n 120 100 80 60 40 20 0 20 40 60 80 100 120\n ASR (World) per 100 000\n\n Age-standardized (World) incidence and mortality rates, top 10 cancers\n\n\n Incidence Mortality\n\n Breast 100.9 15.3\n\n Prostate 73.9 11.5\n\n Colorectum 41.0 13.5\n\n Lung 33.4 25.7\n\n Melanoma of skin 27.0 2.3\n\n Bladder 17.2 3.3\n\n Non-Hodgkin lymphoma 11.7 3.1\n\n Corpus uteri 11.3 2.2\n\n Testis 9.9 0.19\n\n Kidney 8.5 3.0\n\n 120 100 80 60 40 20 0 20 40 60 80 100 120\n ASR (World) per 100 000\n\n\n\nThe Global Cancer Observatory - All Rights Reserved - March, 2021. Page 2\n"

cat(pdf[2])

## The Netherlands

## Source: Globocan

##

##

## Incidence, Mortality and Prevalence by cancer site

##

## New cases Deaths 5-year prevalence (all ages)

## Cancer Number Rank (%) Cum.risk Number Rank (%) Cum.risk Number Prop. (per 100 000)

## Breast 15 725 1 11.9 10.75 3 283 3 6.7 1.64 67 477 784.82

## Prostate 14 580 2 11.0 9.75 2 976 5 6.1 0.92 61 096 715.65

## Lung 13 500 3 10.2 4.08 11 188 1 22.8 3.05 17 878 104.34

## Colon 11 887 4 9.0 3.25 4 730 2 9.7 0.99 36 117 210.78

## Melanoma of skin 8 310 5 6.3 2.89 906 17 1.8 0.24 29 557 172.50

## Bladder 7 417 6 5.6 2.07 1 811 7 3.7 0.33 25 162 146.85

## Rectum 4 845 7 3.7 1.53 1 787 8 3.6 0.42 16 171 94.37

## Non-Hodgkin lymphoma 4 105 8 3.1 1.32 1 462 10 3.0 0.33 13 624 79.51

## Pancreas 3 331 9 2.5 0.86 3 137 4 6.4 0.83 2 519 14.70

## Kidney 3 019 10 2.3 1.00 1 306 12 2.7 0.33 9 426 55.01

## Oesophagus 2 776 11 2.1 0.85 2 139 6 4.4 0.59 3 512 20.50

## Leukaemia 2 375 12 1.8 0.77 1 628 9 3.3 0.33 7 434 43.39

## Corpus uteri 2 202 13 1.7 1.44 537 18 1.1 0.27 8 981 104.46

## Stomach 2 099 14 1.6 0.60 1 240 13 2.5 0.29 3 553 20.74

## Lip, oral cavity 1 558 15 1.2 0.52 331 20 0.68 0.09 5 108 29.81

## Multiple myeloma 1 504 16 1.1 0.45 950 16 1.9 0.19 4 338 25.32

## Liver 1 494 17 1.1 0.41 1 446 11 3.0 0.40 1 518 8.86

## Brain, central nervous system 1 391 18 1.1 0.53 1 037 15 2.1 0.37 4 355 25.42

## Ovary 1 245 19 0.94 0.73 1 068 14 2.2 0.55 3 629 42.21

## Thyroid 873 20 0.66 0.34 178 24 0.36 0.04 3 410 19.90

## Testis 830 21 0.63 0.76 22 34 0.04 0.02 3 838 44.96

## Cervix uteri 773 22 0.59 0.63 253 21 0.52 0.15 2 472 28.75

## Larynx 738 23 0.56 0.26 247 22 0.50 0.07 2 630 15.35

## Mesothelioma 599 24 0.45 0.16 535 19 1.1 0.14 722 4.21

## Vulva 565 25 0.43 0.32 120 26 0.24 0.04 1 948 22.66

## Hodgkin lymphoma 461 26 0.35 0.20 81 28 0.17 0.02 1 953 11.40

## Oropharynx 439 27 0.33 0.17 187 23 0.38 0.07 1 394 8.14

## Anus 283 28 0.21 0.10 62 30 0.13 0.02 943 5.50

## Hypopharynx 245 29 0.19 0.09 94 27 0.19 0.03 503 2.94

## Gallbladder 210 30 0.16 0.06 131 25 0.27 0.03 267 1.56

## Penis 192 31 0.15 0.11 35 32 0.07 0.02 676 7.92

## Salivary glands 185 32 0.14 0.06 63 29 0.13 0.01 670 3.91

## Nasopharynx 79 33 0.06 0.03 43 31 0.09 0.01 286 1.67

## Kaposi sarcoma 75 34 0.06 0.03 1 35 0.00 0.00 259 1.51

## Vagina 70 35 0.05 0.04 25 33 0.05 0.01 212 2.47

## All cancer sites 132 014 - - 33.42 49 008 - - 11.26 461 066 2690.8

##

##

## Age-standardized (World) incidence rates per sex, top 10 cancers

##

##

## Males Females

##

## Breast 100.9

##

## Colorectum 48.4 34.3

##

## Prostate 73.9

##

## Lung 34.3 33.5

##

## Melanoma of skin 27.1 27.4

##

## Bladder 27.3 8.1

##

## Non-Hodgkin lymphoma 14.4 9.2

##

## Kidney 11.6 5.6

##

## Leukaemia 9.5 6.3

##

## Pancreas 8.1 6.8

##

## 120 100 80 60 40 20 0 20 40 60 80 100 120

## ASR (World) per 100 000

##

## Age-standardized (World) incidence and mortality rates, top 10 cancers

##

##

## Incidence Mortality

##

## Breast 100.9 15.3

##

## Prostate 73.9 11.5

##

## Colorectum 41.0 13.5

##

## Lung 33.4 25.7

##

## Melanoma of skin 27.0 2.3

##

## Bladder 17.2 3.3

##

## Non-Hodgkin lymphoma 11.7 3.1

##

## Corpus uteri 11.3 2.2

##

## Testis 9.9 0.19

##

## Kidney 8.5 3.0

##

## 120 100 80 60 40 20 0 20 40 60 80 100 120

## ASR (World) per 100 000

##

##

##

## The Global Cancer Observatory - All Rights Reserved - March, 2021. Page 2

If we actually want to work with the data contained in the document, we need to clean it.

Let’s first try to limit the data only to the table we want to extract:

we can work only with page 2 of the pdf object, and let’s keep only

the part of text between headers “Incidence, Mortality and Prevalence by

cancer site” and “Age-standardized (World) incidence rates per sex, top

10 cancers”. Notice that the . regex catches all characters except for

a new line, so we have to explicitly allow for new lines with \\n and

the use of lookaheads and lookbehinds. Then we can try to separate the

string into a vector where each element corresponds to one line of the

table – read_delim() accomplishes that, although it doesn’t actually

manage to split the data into variables based on the delimiter, so we

need to do that in a different way. We specify skip = 3 to skip the

first three detected lines and start the table with the row of variable

names.

cancer <- pdf[2] |>

str_extract("(?<=(site))(.|\\n)*(?=(Age-standardized \\(World\\) incidence rates per sex))") |>

read_delim(delim = "\\s", skip = 3)

To split the data into variables, let’s first split the variable name.

We can take the variable name, remove leading and trailing whitespace,

and split at any occurrence of at least two spaces – below defined as

the object var. Notice that the original table has an extra header row

that specifies whether the variable names correspond to new cases,

deaths, or 5-year summary statistics. So let’s create a vector that

specifies which of these categories each element of var belongs to,

and combine that with the variable names with a paste() function to

create our vector of desired variable names.

var <- names(cancer) |> str_trim() |> str_split_1("\\s{2,}")

cat <- c("", rep("new", 4), rep("death", 4), rep("5year", 2))

names <- paste0(cat, var)

To split a single column into multiple columns, we can use the

separate() function. However, before we can do that, let’s do a bit of

data cleaning: to make references to the current one variable easier,

let’s rename it to value. Let’s also use the str_trim() function to

remove any leading and trailing white space from the observations. Then

we can use the separate function where we specify that we want to use

the value column as the variable we split, and we want the new

variables to have names specified in the names vector. Just like with

the variable names, we use two or more whitespaces as the separator.

Now the data is correctly organized into cells, but all the numbers are character strings surrounded by whitespace. So let’s remove the whitespace around all cells, and let’s convert all but the first variables into numeric.

To use mutate() across multiple columns at the same time, we can use

the across() function that takes the affected columns as the first

argument and the function to apply as the second. If you want to use a

single function where the only function argument is the variable itself,

you can specify the function simply as the name of the function – see

the first part of the mutate() function that applies the str_trim

function to all variables (defined by everything()). If you want to do

more complex operations, then your function call should start with a

tilde ~, and you should refer to the variable with .x (e.g. if you’d

write var = as.numeric(var) in the single variable case, instead you’d

write ~as.numeric(var) when applying the same function to multiple

variables) – see how for all variables except for Cancer we remove all

whitespace inside the string and convert the result to numeric.

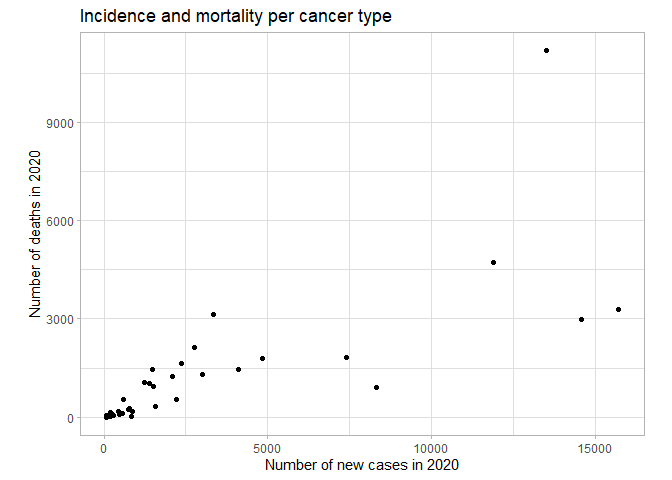

Finally, we remove the row that sums up the previous rows in the original table. Now we have our final, clean dataset of cancer rates in the Netherlands in 2020, so let’s create an example visualization: the scatterplot below shows the relationship between new cancer cases and cancer deaths per cancer type, which shows the relationship between these two numbers a lot more clearly than the original table did.

cancer_tidy <- cancer |>

setNames("value") |>

mutate(value = str_trim(value)) |>

separate(1, into = names, sep = "\\s{2,}") |>

mutate(across(everything(), str_trim),

across(-Cancer, ~as.numeric(str_remove_all(.x, "\\s")))) |>

filter(Cancer != "All cancer sites")

ggplot(cancer_tidy, aes(newNumber, deathNumber)) +

geom_point() +

labs(x = "Number of new cases in 2020",

y = "Number of deaths in 2020",

title = "Incidence and mortality per cancer type") +

coord_fixed() +

theme_light()